This is the first in a series of posts which are concerned with software development, specifically with the writing of Feature Files. I started this blog because I imagined that I had something interesting to say on a number of subjects. On most of these, my musings are of limited appeal, and will doubtless be lost amongst the vast quantity of more well-informed or more eloquently expressed opinion. On this particular subject though, I discover that there is relatively little published material, so I feel that I might be doing a service to others in writing about what I know, as well as satisfying my desire to commit pen to paper on whatever comes to mind.

My particular concern is the use of Feature Files as long-lived documentation that is valuable to multiple stakeholders. Here’s a diagram of the commonly regarded “Holy Trinity” of functions of a Feature File.

This post is mostly about the background to my particular interest in the largest of the above circles. For the last twenty or so years, I’ve worked in Financial Services, in Investment Banking. Like many in my field, the years since 2008 have been concerned with satisfying the increasing amount of regulatory oversight of our activities. My first involvement in this area was in writing a system to satisfy the regulatory requirements to protect client assets held by the bank in the event of its demise.

Regulators are not only concerned that firms like mine do the right thing, but also about how they do it. Part of this concern behoves us not only to to demonstrate that we understand how our systems behave, but also to provide an audit trail of documentation proving that understanding.

The system in question was one of the first that we developed using a newly adopted agile development methodology, a key part of which was the definition of the system behaviour in terms of Feature Files.

We knew in advance that the regulators and auditors would descend upon us as soon as the system was operational, and we also knew that their first demands would be to provide the standard documentation around around a project of this type – a BRD, functional and technical specifications, all of the usual rotten artefacts of an old-school SDLC. We would only have our Feature Files to fall back on, so we had to make them good!

This is where my interest in the use of Feature Files as living and lasting documents stems from. My concern is primarily about making feature files as readable and understandable as a finely crafted Word document, so that months or years after their initial implementation they still stand up as accessible descriptions of system behaviour.

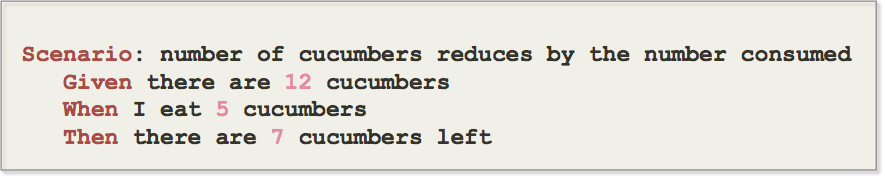

Enough already with the preamble. So that this first post is more than just an essay, let’s try an exercise. Here’s an example from the Cucumber documentation describing the scenario outline gherkin syntax:

All well and good. Presumably, if you have read this far, you already know something about Feature Files, and so can understand what’s going on here. But just for the sake of argument, try putting another hat on – say the hat of a relatively technically illiterate reader. Ask yourselves these questions:

- What does the scenario outline header tell you?

- How do the “Given, When, Then” steps actually read in english?

Fair enough – this is a feature, illustrating a basic subtraction algorithm, that would probably never be necessary in the real world. However, suspending your disbelief for a moment, how would you rewrite this scenario to make it more easily understandable to the casual reader?

There are no right or wrong solutions to this exercise. My point is that the writing of scenarios in a feature file to make them useful as long-lived documentation is an art rather than a science. To illustrate that point, I provide two possible solutions which have been provided when I have workshopped this subject.

The first takes the example as given, adjusts the example column headers to express the problem (simple subtraction) in a domain language that suits it, and makes some simple changes to the step wording to accommodate those changes. It also adds a more meaningful scenario header:

The second example takes an entirely different approach. Understanding that the use of more than one example is redundant in this case, it proposes a different scenario style entirely, using what I call the “narrative paragraph” style:

Scenario styles will be the subject of the next post in this series. For the moment, I hope that this exercise will encourage you to start thinking more about the language of your Feature Files.